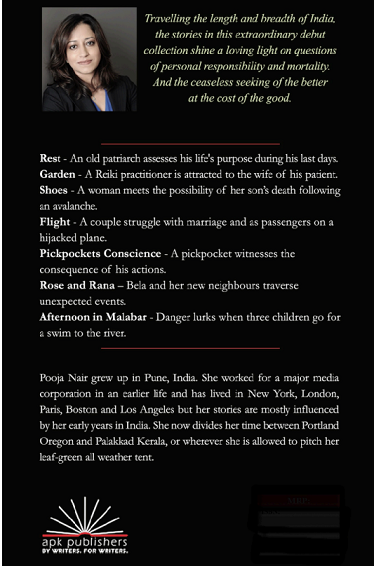

A plug for Pooja Nair’s book of stories, ‘I Was With You’ .

Death, or rather the fear of it, struck Vasant Rao with unexpected suddenness, when he turned eighty-four. A celebration would be organised with friends and relatives who would come with good wishes on this occasion, called Sathabhishekam in Sanskrit. A day, when you have seen a thousand full moons, a time to pursue Moksha with renewed vigour.

Initially he had been quite excited about the grand function, a birthday party in his honour. But then the symbolic meaning of the day filled him with fear. Who would get all his things, his house, his cars, his silk shirts, his tailored suits? But most of all his estates, coffee plantations lovingly tended-to and profited-from. After this outstanding life, was his end to be no different from anyone else? Would he, Vasant Rao, cease to exist too?

So far for him, death was far removed from him, something that happened to the other. When he was seventeen, he had seen his father die at close quarters. His father had suffered, for a long time, and especially the last week before his death had been a horror to watch. It was like life was being snatched away from an unwilling man bit by bit in a terrible fight till the end. After life had passed from his father, he was washed and dressed in white and laid down on the top of a white sheet. He had seemed a different man, younger, almost handsome, with his big nose and gaunt thinned-out face. Within the family there was relief, like a task completed, a cupboard cleaned out. He had wondered then, where to all that fight in his father had been sucked away, replaced instead by a peculiar inert heaviness.

For years Vasant Rao was in the habit of going every day for rounds of his extensive estates. A few months before his birthday he had felt faint and tripped as he got out of his Audi SUV. He had put out his hand to break the fall which caused cracks in the bones of his left hand and a fracture in his forearm. The skin split where his head hit the ground and blood had streamed down his face into his white beard.

Initially the doctor said that the head injury was not serious. But the fall shook him and his routine. He was recommended rest. In spite of the rest, x-rays showed that there was no sign of healing in his arm. This did not seem to surprise the doctor, he reviewed his chart and said to himself – Oh ok, eighty plus years old. That comment annoyed Vasant Rao, as though it made sense to the doctor that the body had not bothered to fix something so close to expiration.

A week after the fall he developed a persistent headache. Some additional tests were done, and the doctor said the fall had caused a concussion. At his age, surgery was out of the question. The concussion would eventually cause a stroke, but it was difficult to say when, it could be a week or two years. The doctor recommended that he stop doing his daily drive through the estates. That did not matter in the practical sense, the daily survey was a superfluity, like a champion’s victory lap. But it used to take up the better part of his day and in its absence, there was a vacuum. The vacuum filled with thoughts.

His life had been his work. He had married a simple woman who gave him no trouble and a son. About six years ago she had died, as quietly as she lived, in her sleep. He lived now in this big house alone, other than the servants. His son was married, with children. He worked for a publishing company in the United States.

It was true that nothing had come easy to Vasant Rao. He had got a small plot of land from his father in the city centre of Mangalore which he sold. With that money he had bought four acres of land in the hills of Coorg. Everyone had said that he had gone quite mad, that he should have used his education as a lawyer in the city instead of going into the forest, the kind of forest where no man should be. What would he grow there and how would he find labor; he did not even speak the local language.

But Vasant Rao had a plan. Indians were mainly tea-drinkers but opportunities for exporting were opening up in the country and Coorg was ideal to grow a high value crop, Arabica coffee, for export. The first years were hard, but he knew he was onto something and eventually business flourished. His land bordered a national forest area called Bhadra. Later, using influential connections he started buying large tracts of the forest for a very cheap price. Even after paying commissions to the government officials, it was a great deal. The land was like gold and along with coffee he was able to grow cashew and all kinds of high value spices like cardamom, nutmeg and pepper.

He started exporting to Europe and East Asia and was called ‘Coffee King Vasant Rao’ in the newspapers. But he found it narrow and preferred the epithet Prithvi Vijayan (Victor of Earth) Vasant Rao. He planted stories in the press which used this name, but it did not catch on. His estates gave tours of the plantations and the coffee bean making process to tourists and the tour ended at a statue, his likeness at forty, on an elevated hexagonal base made of red oxide on which he etched his name with the desired prefix, so at least history would remember it.

As his eighty-fourth birthday approached, he slept badly, if he slept at all, and often woke up in a sweat. Much worse than the pain in his arm, the darkness of the room filled him with deep dread. What was the meaning of all this that he had collected, when there was no container service at the end?

He had a servant Santosh who had been with him for about fifty years and still attended to most of Vasant Rao’s demands himself. He made Santosh shift his bedding to a corner of his room because he was nervous of being alone, especially in the night.

One night was especially bad. He had slept, well after midnight, and had woken up feeling miserable, like the discomfort a person would feel without a blanket on an icy night, though he was in a four-poster bed with a mattress that contoured his spine and a comforter made of down feathers.

He had dreamt that he was being chased by half a dozen elephants. He had a head start but they were closing in. Finally, he jumped into the river and started swimming to the other side thinking they would stop following him, but they all splashed into the water one after the other; it was hardly knee deep for them and they seemed to be making ground faster than on land. The current was strong, and his arms started hurting. He couldn’t swim much longer, and he sensed that any minute now a big trunk would circle his waist and raise him high, aloft.

Vasant Rao woke up with a start, his arm was throbbing with pain where it had broken, and the room was dark like there had never been light in it. His heart was beating fast and his head hurt. This was not the first time he had seen this dream. At the other end of the room, he could hear the deep breathing of Santosh, sleeping as soundly as only a fool can.

In the early years wild elephants would regularly foray into his plantations. Bhadra had been their home after all and they don’t forget easy. Vasant Rao had put up high-tension electricity fences around his estate to stop them. Once a six-year old elephant had died there of electrocution. Long after, its mother would come back to that fence. Vasant Rao had seen her during his drive-throughs in the estate. She stood at the fence within whatever little remained of Bhadra, tall and tranquil, perhaps reflecting on whether she could have been a more watchful mother, before turning back into the forest.

Vasant Rao sat up, had a glass of water and tried to go back to sleep but his mind was restless. Since his wife had died, his son had visited only once in the last six years. While their mother was alive, he would come every December like clockwork, with his wife and children. He would call him, once a month, if that. Whereas, his mother he would call twice or thrice a week. He used to get all his news from her. Photos of their grandchildren were sent to her and stories of their antics would be shared. However, with him, these calls were an awkward affair. His son asked after his health and the weather and then wanted to hang up like it was a chore to talk to his father. And now, why was he coming for the birthday? Had he been told that his time was limited? He would have discussed it with his wife and with their friends in the foreign land. Hearing of the accident he would have been asked, how old is your father. And they would respond – Ah ok, eighty-four years old! The situation explained, an acceptable expected context for any outcome.

Anyway, his son did not care. He knew nothing of the plantations. Vasant Rao had discouraged any involvement from him; he was the unambitious bookish sort like his mother. In any case, the plantations really needed just one leader and labor who would do his bidding.

The sun, lazy as a sloth, finally came up after the long night. And Vasant Rao felt more exhausted than he did when he went to bed the night before.

Santosh had woken with the sun, rolled up his bedding and was back in an hour to dust and clean the room. He was a good foot shorter than Vasant Rao so normally wasn’t in his field of vision. But as Vasant Rao lay in bed, he watched Santosh mopping the floor. He was squatting and swinging his supple back almost 180 degrees in front of him with a wet mop. The floor area below the bed got his special attention; he bent forward and receded into a child’s pose, again and again so no corner was missed. He was probably around the same age as Vasant Rao, but he moved with ease, twisting his torso fearlessly.

“Can’t you use a stick to mop the floor? At your age should you be bending and squatting on the floor like this?” he asked with more jealousy than concern. “Or tell one of the younger guys to do it.”

“I can clean better without it. I don’t mind. It keeps me healthy.” He smiled happily at his boss’s concern.

“Haven’t you saved enough? Don’t you want to retire, stay with your family now?” Santosh was his oldest servant who knew exactly the way Vasant Rao liked things, old or not, he would never want to give up Santosh, but he was in a strange mood this morning. “You have a daughter, don’t you? Doesn’t she ask you to stay with her?”

Santosh went away on holiday to his village every year in May, the rest of the year seven days a week he was at the beck and call of Vasant Rao.

“Yes, she does, all the time. Maybe one day when I am old, I will go for good.”

“You are old.”

“They have a busy life and I feel bored sitting around in her house, when it is here that I am needed. But we talk on the phone,” he said moving on to dusting the side tables.

“How often?”

“Once a week, sometimes more.”

“Ok leave me alone. Now! You can do your cleaning later,” Vasant Rao snapped.

Lack of sleep was making him irritable. All his life he had been driven by the need to be acknowledged as special. There had always been goals to achieve, adversaries to beat, but now as life was winding down, he felt no different from anyone else, he was unclear about what the field of action was, to assert his specialness. He was just an old man with a lot of money that he did not need and a son who did not care. Even his desired sobriquet had not caught on. He felt quite sorry for himself.

Could it be that this specialness that he had pursued all his life, favourably called ambition, was really an illness that had caught up with him in the form of this headache from hell. Was the fall that triggered it just a coincidence. Because what did it really mean to want to be the best? It meant you desired that others were worse off. That can’t be a good thing, his wife always said so. He stayed in bed late, thinking of all this.

Around afternoon he got up and sat at the table with a new resolve. He would write, a diary, his life story, with a chapter for each achievement and that would somehow reveal to him what the epilogue, that special last chapter should be.

In a structured way, like he did everything else, he started making a record of his life. He wrote feverishly. When he couldn’t sleep, it did not bother him anymore. His sleeplessness, his headache, his waning life, all of it he poured into this ceaseless activity.

“Aren’t you lucky that it’s your left arm thats broken and not the right?” Santosh said one evening. He had unconsciously spoken his thoughts aloud and regretted it because Vasant Rao was short tempered. And normally such a statement, suggesting that there was anything at all fortunate in this situation would have angered Vasant Rao. But he was too tired for anger.

Encouraged by the lack of reaction from Vasant Rao, Santosh added, “Even without all this writing, I know what I will do last.”

Vasant Rao ignored him for a few moments but then couldn’t resist. “What’s that?”

“The last thing, the very last thing that is – I will exhale.”

“What?”

“Exhale, you know. Breathe out. The very last breath out, and for the first time in my life it will not be followed by a breath in. And then I’ll know that it’s all over. Will be the same for you. What more?”

“You’re a smart one, aren’t you?” Vasant Rao snapped feebly.

From the time he had started writing his headache had steadily increased, till he had Santosh tie a woolen scarf tightly around his head. He did not take pain killers because it made him groggy and he couldn’t then remember specific details of people and places. Since he had set himself this mission of recording his life, just like everything else he had done, he could not rest till it was accomplished. He had this ability for single-minded effort and once he had set forth on his mission, he did not again question or doubt the eventual purpose of such a record, till it was done. He split it into chapters, and organised as he was, he first gave them titles like childhood, land purchase from x, marriage, first export deal with Germany, etc.

He rejoiced at the memories of his childhood, still surprisingly vivid. Of going to the pond near their house with his mother. Playing in the water, hearing his mother’s shouts telling him to come back or he’d catch a cold. He would laughingly ignore her summons till she finally swam to him to gather him in. As he wrote, he saw a lighthearted careless mama’s boy. His determined success would have been a shock to his father, who would scold him for being too happy-go-lucky. The big house of his childhood was as much filled with breeze as with his mother’s voice. Cooking, ironing clothes or even while just sitting in the balcony she was always singing. He kept his pen down and tried to remember her strong beautiful voice. He had not thought of this for sixty years, he was surprised he could even remember it. For a moment, he felt that he was back in her sanctuary.

The death of his father was the end of bliss, especially the way it happened and the next summer his mother had passed away too. Suddenly he was solely responsible for himself, for the house, even before he had turned twenty. The big home without his mother was lifeless. No one in his family had ever been in coffee, so he did not know where he got his idea of growing coffee. Perhaps a newspaper article had triggered it. He had ignored the advice of his extended family and had made inexplicably big decisions in very quick time. He sold all the furniture, then he sold the house and took an overnight bus to Coorg with just a backpack. He wondered where that audacity and that resolve came from.

Without thinking, he wrote, and he wrote. He had nothing to write in the chapters he had titled his marriage and children. Yes, he had got married, yes, he had children, there was no more to report. His export deals and business growth which he wrote extensively on, did not fill him with any great feeling of achievement either. He had spent a lifetime in the cultivation of a superfluous habit, a stimulation that every morning men everywhere succumb to, out of habit. It was just something he had done like a potter spins his wheel, but he had not moulded the clay. And when he had seen that the clay was formless, without meaning, instead of using his hands to shape it, he had spun the wheel even faster.

And then the day before his birthday he finished, and he read what he had written. It made him weep, because he realised that there had been a continuously diminishing joy in him. The worst had happened early in his life, and there had been nothing he could do but lash out. And the world had relented to his aggression and given him whatever he demanded. There it was, his audacity, his whole life, was an expression, a manifestation of his misery, nothing more. He saw that his mistakes were many. Petty corruption to get ahead. Indifference to his wife. She had learnt to expect nothing from him, had even forgiven him. She had made her peace with it while he had been unaware. Thinking of all this, he went to bed.

In spite of his morose state of the day, he slept, his mind a little easier. Because even as he had read it another time, he had been bored. He felt a detachment from it. Sad as it was, it was still just a story. Eighty-four years, though he had spent on it, all his time really, it was still just a story, a few notebooks worth, nothing more.

Sometime before dawn he exhaled, deeply.

Then it was the morning of his birthday and sunlight streamed in. His pains and aches were gone, his suffering from them was not severe any more.

There was a clarity in Vasant Rao this morning. He looked at the notebooks on the table. A simple story, mistakes and all. The ease in his body after what seemed like a decade of discomfort made his bed feel like his mother’s lap. He settled in even more into his bed and smiled, a big smile, for life, for the sun, for the morning.

When he closed his eyes again, his mind took him back in time, to a moment in his life, so real, like he was there again. It was dawn, Vasant Rao, dynamic, all of forty, with his imposing height of six feet and some, stood, his foot on the top of the wheel of his jeep, his hands at his waist, the new owner of most of Bhadra. Now Bhadra is not a park, it is a tropical forest, the Western Ghats, life itself. Hundreds of unique bird species. And wildlife – tigers ten feet long, chitals, bears, over two hundred elephants, more than 50 types of snakes, forest fed rivers, basically thousands of diverse life forms.

Contractors with machines, and saws and bull dozers stood in front of him waiting for his word, like he was a general.

Raze it all, he had bellowed to them in an ugly voice.

And he watched as they set forth. It had taken six months to turn it all nice and flat, ready for coffee, twenty kilometres square at a time.

Tears streamed from Vasant Rao’s closed eyes into his white beard as he heard the whoosh of the trees that had fallen that day, every soundless scream, every scrambling living thing’s fear he felt like it was his. But it was a grief without sorrow, a fear without panic, it was just there, it was him, like the stump of a long-amputated limb or even more reconciled, like a genetic defect.

And then he decided with a certainty he had not had since his youth what his last chapter ought to be. Bhadra. He could try to restore the forest. In twenty or twenty-five years, perhaps, the forest would start coming back.

Extinction was the pessimists view, it could be reversed. Prithvi Vijayan what a monstrous name he had wished for, the name he wanted was Prithvi Vallabha, a friend of earth. And he would become it too, you see once Vasant Rao sets his mind on something, he does not rest till it is accomplished. He has the audacity to rise again. He has this ability for single-minded effort and once he has set forth, he does not again doubt the eventual purpose of such a mission, till it is done.

And then a strange thought came to him. Why was his pain gone? What did this sudden, uncharacteristic insight, that had eluded him all his life, mean?

The sun was streaming into the room, with an otherworldly brightness.

Santosh came in and started cleaning the room.

Vasant Rao sat up and wished him good morning, but rather rudely Santosh did not reply or even turn around and acknowledge him.

Santosh was careful to make little noise, he did not want to wake his sleeping boss. Typically, Vasant Rao was a light sleeper but today he seemed to be sleeping like the dead. Santosh was in two minds on whether to proceed with his cleaning or not and decided against it. Better let the angry old man sleep some more and get his rest.

‘There was time. The first guests for Vasant Rao’s birthday would not arrive till late afternoon’ – Santosh thought as he tiptoed out, closing the door softly behind him.

—————————

Available in local bookstores and online.

Eswar

November 23, 2019

Thank you BR 🙂.

LikeLiked by 2 people

meera

November 24, 2019

I’ve read Aparna’s articles in the Hindu… I rem one poignant one of the mylapore Kapaleeshwarar temple in the wee dawn hours.. is this the same author?

LikeLiked by 1 person

brangan

November 24, 2019

meera: Yes, the same.

LikeLiked by 5 people

tonks

November 24, 2019

Farmers fare better, but only just. The backbreaking work they plough into an acre of paddy nets them about two hundred a day. Palm tree climbers? Roughly two hundred and fifty, but only during a limited, unpredictable season

Not in Kerala, though. Field workers charge Rs 800-1000 per day, work days are 8 30 to 5 pm with a one hour lunch break and a tea break. Specialized skills labourers (masons and carpenters and painters all charge higher per day rates). Coconut climbers use machines and charge much more : Rs 50 per coconut tree, and they manage upto 25 trees in a half day (which works out to Rs 2500 per day).

But with all this, I think that maybe they would prefer their children get educated (as they all are) and into less strenuous jobs. Probably why most of the manual labour these days in Kerala is done by migrant Tamilians and N Indians (all of the latter clubbed together irrespective of the state they come from, as “Bengalis” : sweet revenge for them calling all of us in the Southern states as “Madraasis”).

LikeLiked by 3 people

Anu Warrier

November 24, 2019

Thanks for this, BR. That introductory passage hooked me; what powerful writing! I must buy this book.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Krishnan Viswanathan (@matungawalla)

November 24, 2019

Thanks for the pointer BR. And thankfully Amazon US has it in stock. Looking forward to reading it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Anu Warrier

November 25, 2019

@tonks, ha! 🙂 I wondered whether I should point it out – the man who comes to clear the grass off our grounds charges 850 per day with – as you say, an hour’s break for lunch, and a tea break.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Anu Warrier

November 25, 2019

Done! 🙂 Book ordered, and now the wait…

LikeLiked by 1 person

krishikari

November 25, 2019

This book was already on my list! I’ve been wondering if there was anywhere other than Amazon to buy it? Do I have to wait till I’m in india next month and able to visit an actual bookshop?

LikeLiked by 2 people

Aparna Karthikeyan

November 25, 2019

Hi! It is up on Amazon UK and US (print-on-demand) and also on Kindle. I’m really not sure about bookshops – I know sellers in India are stocking it . Many thanks for the interest!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Aparna Karthikeyan

November 25, 2019

Thanks a ton, Baddy, for sharing this on the blog!

I’d love to hear from anybody who reads the book – will really appreciate your thoughts/ feedback/ comments!

LikeLiked by 1 person

meera

November 26, 2019

@Aparna Karthikeyan: have hopped into your site and I can tell this book was a labour of love as is with all books and authors 🥰 your posts on the blog are the ones in the book? Have ordered your book so don’t want to read on if they are the same ☺️

LikeLiked by 1 person

meera

November 26, 2019

Sorry for the very many typos… sometime auto correct is not so correct 😂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Aparna Karthikeyan

November 26, 2019

Hi Meera, thanks much, that is more of a companion blog, hoping to post what did not make it to the book – edits! ,- and also photographs/ videos. Excerpts from the book are not up there. There’s one here, on Baddy’s blog from the intro, and then Scroll, Huff Post and News Minute carried some bits. Thanks much for your interest, appreciate it!

LikeLiked by 3 people

Anantha Padmanaban R

November 29, 2019

Certainly a relevant book in today’s times. Another great book covering a similar theme is “Everybody loves a good drought” by P Sainath, the master in rural reporting

LikeLiked by 2 people