Spoilers ahead…

When Saeed Mirza made Albert Pinto ko Gussa Kyun Aata Hai? in 1980, a little after the Emergency, he seemed to be taking on Bachchan’s Angry Young Man of the 1970s and asking: “Okay, now, in this new decade, what is the young man angry about?” It’s not that his parents have been killed by some villain wearing a horse-pendant bracelet. It’s not that his father was branded a thief and had run away. It’s not that he’s illegitimate, and his father abandoned his mother. Indeed, at first, the film’s lower-middle class protagonist (Naseeruddin Shah) seems to have no real reason for his anger but the fact that he has a short fuse and he keeps blowing up at everything. He blows up because he doesn’t like his girlfriend’s boss flirting with her. He blows up because the country is going to the dogs. But at first, his anger is superficial. He keeps complaining and commenting about this and that, but he doesn’t really know anything. (He’s stumped when asked about the Minority Bill.) The film, thus, is his awakening. It’s only at the end, after his mill-worker father is beaten up by the very capitalists he worshipped earlier, that his rage truly takes root. The title question is answered. He turns into Bachchan, but instead of a single villain, his anger is now against an amorphous System.

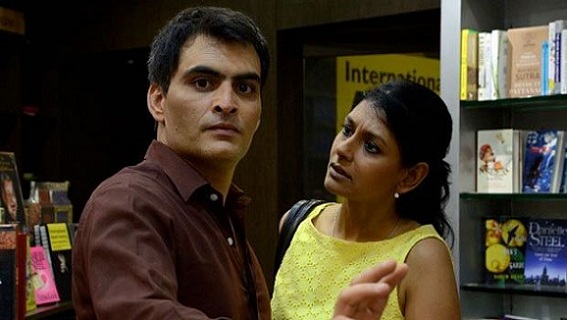

There’s no such transformative arc in the new film bearing the same name, a “conceptual remake” directed by Soumitra Ranade. This Albert (Manav Kaul) is angry, too — but unlike his predecessor, he’s upper-middle class. His father was a diplomat and was implicated in a scam. That’s one reason for his anger. When his girlfriend Stella (Nandita Das) tells him she is pregnant, he asks her why she wants to bring new life into this world. He’s quit his job. He’s cancelled the flat he’d booked, where he was going to build a life with Stella. In a bookstore, he sees a TV news report about horse trading in the parliament, and he wonders, “Mera rate kya hai?” He turns to a customer and asks, “Aap ka rate kya hai?” Unlike the Naseeruddin Shah character, this Albert isn’t venting out his anger. He’s stewing in it. And he goes nuts.

Without a word to anyone, he takes off to Goa with a gangster’s underling named Nayar (Saurabh Shukla), on a mission to kill a few men. Maybe he thinks it’s his therapy. Some people use a punching bag. He’s using a loaded gun. But is he? How much of what we see is real and how much a reflection of the fever-dreamscape of Albert’s mind? A cop says, “Yeh aadmi samajh mein nahin aaya.” He’s right. The question-bearing title could have been Albert Pinto Kaun Hai? Is he on the verge of a nervous breakdown? Is that why Albert keeps seeing Stella in every woman he meets along the way, including a sex worker? Is that why Rahul De’s camera keeps skewing the angles we see Albert in?

There’s certainly a case to be made that the country has changed so much since the 1980s that surrealism is the only lens through which an Angry Young Man story can be told anymore. But this conceit isn’t carried through convincingly. Albert keeps saying things like “we are all crows, ped pe baith ke tamasha dekhte hain” and we’re meant to recall the crows from the opening scene. Albert looks at nomads and wonders why they are so happy. A messagey bit like this is so literal (it’s right out of a Panchatantra fable), it kills the woozy nature of the rest of the film. A far better scene is the one where Albert asks why a forest dweller (Omkar Das Manikpuri) is so happy when he has no electricity or water, no hospital facilities. The man won’t stop grinning, so Albert squashes the burning end of his cigarette on his hand. Albert seems to be saying, “Do you feel the pain I am feeling every day?”

The film proceeds on two tracks. Apart from the one with Albert, we have the one where a cop (Kishore Kadam) is trying to figure out Albert’s whereabouts with the help of Stella and others. The conventionality of this device is at stark odds with the bizarreness of the Albert track (even if this was intentional, it remains another conceit that never comes to life), and it quickly becomes taxing. The film itself is taxing. Fans of the 1980 film may enjoy the compare-and-contrast (this Albert, too, has a God-fearing mother, a guitar-playing younger brother), but consider the scene where Stella’s father threatens Albert and asks him to stay away from his daughter. We realise we hardly know the man. In the earlier film, we came to know him as well as Stella did. The screenplay is a jumble of straight-up and strange scenes, and the fine actors never settle into a rhythm. This “conceptual remake” could have used less concept, more thought on why they were remaking the earlier film in the first place.

Copyright ©2019 Baradwaj Rangan. This article may not be reproduced in its entirety without permission. A link to this URL, instead, would be appreciated.

Mank fan

April 18, 2019

Nice to see you review this film. The film suffered from a limited number of screens in Mumbai and there is absolutely no buzz around it. I was hoping this would atleast be a decent enough followup to the original because the conceit is still relevant. Having said that, I donot think the original is a particularly great film, it doesn’t work in its entirety. Loved Naseer’s performance though – sheer craft and ingenuity.

LikeLike

Abeer Varan Dey

May 25, 2019

Distributors and film makers kindly bring it to Amazon Prime or Netflix.

LikeLike